Random and sparse attention for GNNs

Exploring Random and Sparse Attention Mechanisms for GNNs

Many application domains of neural networks involve graph structured data, such as social networks, molecular interaction networks and gene regulatory networks, which tend to involve large numbers of nodes and connections. For example, social networks might contain millions of users of a social media website, or gene regulatory networks tends to include tens of thousands of nodes, representing genes. The advent of graph neural networks allowed users to develop deep learning models that capture the underlying information in graph topology. Although many different mechanisms have been suggested, the broad class of neighborhood aggregation has proven to be a flexible class of algorithms.

Among these methods, Graph Attention Networks (GAT) showed state-of-the-art performance in a wide range of graph classification and node classification tasks. GAT uses an attention mechanism to calculate edge weights for each layer to adaptively scale the neighbors’ contributions based on their node features. Moreover, GAT also allows multi-headed attention to compute multiple sets of attention coefficients (edge-weights), enabling the model to have additional expressive power. However, computing attention along every edge adds to the computational cost of operations, and can make scaling GATs to large graphs infeasible.

A subsequent work, introducing Sparse Graph Attention Networks (SGAT), shows that having different parameters to learn multi-headed attention has limited utility because most learned coefficients are redundant and dramatically increase the risk of overfitting. SGAT attempted to alleviate this problem by learning a single set of edge attention coefficients across all the layers while also learning a mask to drop relatively less important or redundant attention scores. The added sparsity constraint makes sure to greatly reduce the number of edges, and the edges to be removed are learned to simultaneously maximize the predictive accuracy. Even though, SGAT works with a significantly smaller set of edges, it still suffers from similar runtime and memory issues due to still computing all the attention scores and having to learn additional parameters for the mask.

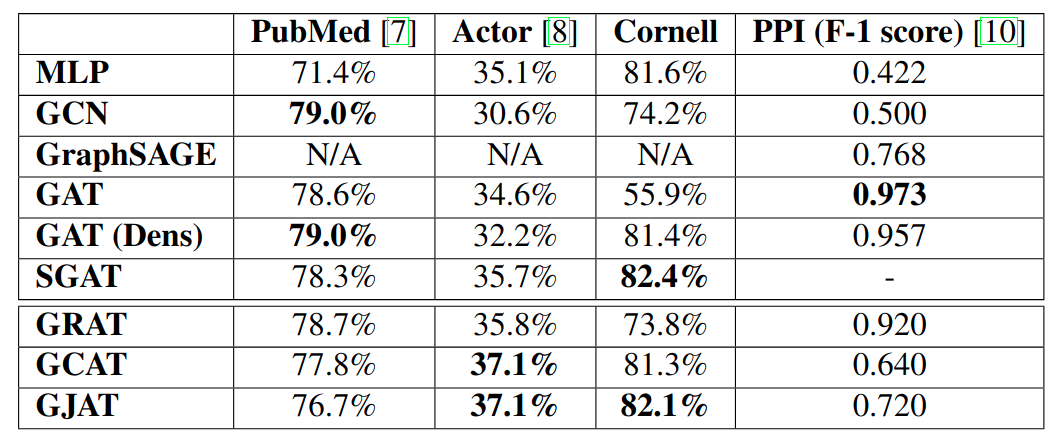

In language model domain, recent works Synthesizer and Big Bird attempt to address a similar problem, and improve the scalability of the attention mechanism of transformers to longer sequences. These models, among other techniques, explored random attention as a potential method to capture long range interactions without attending to the entire image, significantly reducing the memory and runtime complexity. The motivation behind this approach is that over many successive transformer layer, information can likely propagate through a random path between any two tokens even if they don’t directly attend to each other. In this project we explore a similar class of mechanisms to improve the memory and runtime complexity of the GAT by employing various methods to prune out edges from the graph. We reason that this may improve the runtime and memory complexity of Graph Attention without hurting the performance, since even if attention is not explicitly calculated along an edge, information can still flow between the two nodes through their shared neighbors. Specifically, we explore a randomized edge dropping method (GRAT), a node similarity-based edge pruning method (GCAT), and a node neighborhood-based similarity pruning method (GJAT). The goal of our analysis is to explore how a non-learning mechanism for sparsification can help GAT models scale better to larger inputs. We hypothesized that randomly sparsifying attention might have an even smaller performance trade-off for graph neural networks due to the added information present in the graph topology. Through our experiments on four benchmark datasets, we discover that for disassortative graphs, similarity-based sparsification mechanisms perform competitively while significantly reducing runtime, however, for assortative graphs, performance drops quickly with edges removed.